Theory of mind is a bit tough to tackle, even for me. I don’t have a very strong background in cognitive neuroscience, but I know that even within the field it is used very differently between studies. It is presumed that autistic people don’t know how to interact with non-autistic people because they lack “theory of mind” (which is generally thought of by other people as “being able to take someone else’s perspective”), so therefore we don’t know how to we should respond to others in the correct way. I am going to break down why this concept is so flawed and how the theory of mind argument is often used to negate the experiences of autistic people.

There are many problems with this line of thinking.

- Autism research has most often judged autistic people’s “theory of mind” based on how well they interact with non-autistic people, and only non-autistic people.

- Autistic people likely interact with non-autistic people (or assumed to be non-autistic) 90% of the time.

- Non-autistic people likely interact with autistic people less than 10% of the time, and even less of the time are interacting with openly autistic people (1% of the time?).

These are just generalized, fake numbers, but the point still stands. When have non-autistics been tested on their ability to “read” autistic minds? And to understand their processing and their intentions? Very rarely so.

The Biggest Issue

Autistic people have different sensory experiences than non-autistic people do. We have to suppress the urge to turn our head when we hear a sound, or look somewhere else when we see movement or a flashing light. Theory of mind experiments don’t take this into account.

It often surprises neurotypicals when I tell them that I relate more to another autistic person (no matter their traits) than I do to a neurotypical person. They are surprised because I am “so good” at communicating (exhaustively) their way, and trudging through their customs. That is not to say that I do it easily, just as it is not easy for a neurotypical person to understand autistic people’s body language/tone of voice and intentions/emotions, although it is much easier for them to write off their unawareness of autistic customs by saying we have a “bad theory of mind” which prevents them from understanding us.

The idea that autistic people do not have theory of mind simply because we do not access the neurotypical experience readily and are not invested in the social world is ludicrous. It is like telling a neurotypical they don’t have theory of mind because they can’t hear that buzzing sound next to me, move their facial muscles too much, talk too loud (why can’t they tell my ears are hurting when I blink so much? a clear signal!), and don’t use echolalia to communicate.

Neurotypical Assumptions

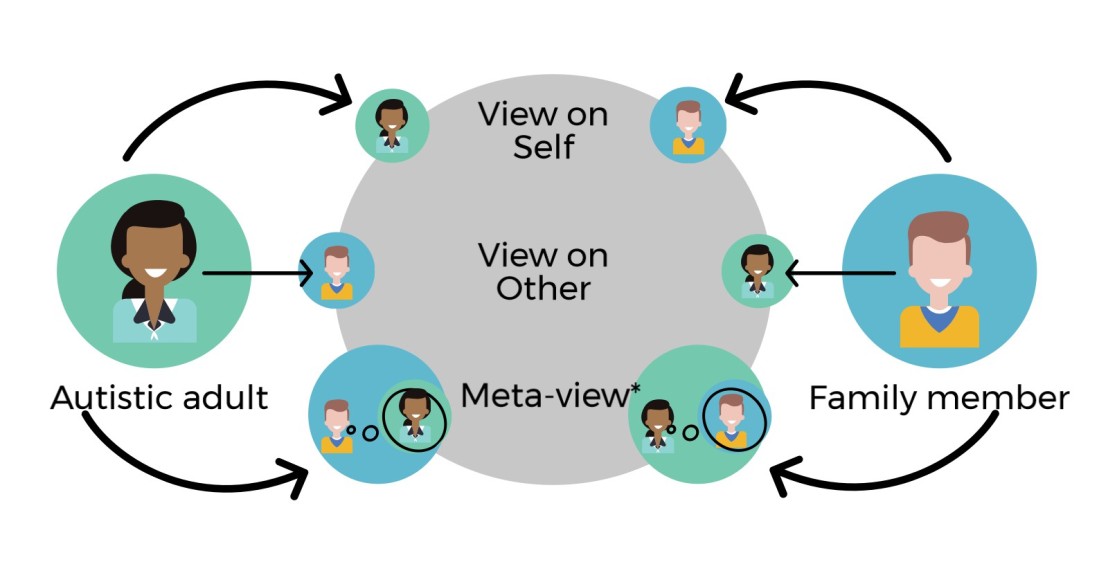

This video about the double empathy problem and the accompanying research article highlight some very important and common misconceptions that come into play when people think of autism.

Diagram from Heasman & Gillespie (2017).

Here are some things that can happen when you tell people (or like me, write about it on social media) that you are autistic.

They somehow assume you are:

immediately more ignorant than you used to be,

immediately more strange, even if your behavior stays completely the same,

very self-centered (everything you now say is assumed to be because you want things to be about you, even if you are trying to be nice),

or they are confused as to how to interact with you, even though they have for weeks/months/years before.

These assumptions many non-autistic people make about us are then bolstered by the “you lack theory of mind” argument. Once coming out as autistic, the idea that you do not have “theory of mind” can be used against you by non-autistic people to reduce the impact of your words, or have them ignored altogether. It is also a way to gaslight your own emotions and the impact others have on how you are treated. It is a way to easily dismiss their own problems and assumptions they have about us, and simply project them onto us instead.

Media Portrayal

It does not help that there have been an absurd number of movies and tv shows that often provide infantilized autistic characters which involve being very smart while also being either pitied, their “deficits” of literal thinking or sensory issues used as a punchline (Big Bang Theory, Atypical), or their savant-ness used as inspiration porn with the backdrop of being autistic (The Good Doctor). These characters are consistently portrayed as off-putting, embarrassing for others to be around, selfish, incapable of learning from experience, lonely, and struggling to make friends, or not caring whether they have any.

Is it any wonder that non-autistic people hear the words “I’m autistic” and start pitying and/or infantilizing us?

An argument that neurotypical people lack “theory of mind” for autistic people:

They don’t understand that:

- I’m not shy or sad when I look down, I’m regulating my senses from all the auditory stimuli going on.

- I’m actually paying attention when I’m not looking at your face. I can actually process your words better.

- My voice isn’t “defensive” and I am not arguing – I am simply very interested in what I’m talking about and talk quickly.

- I am not talking because the current topic makes me stressed out and emotional – it is not because I cannot think or do not have opinions on the matter.

- I am not “nervous” – I am confident. That is simply my body language, especially when I am comfortable, such as standing still, and not looking at people’s faces while I’m talking, and wringing my hands under the table. I do not project my voice super loudly because I can hear my voice very well when I talk, unlike most neurotypical people, so I do not need to shout. I have very good hearing.

Imagine if I rolled my eyes and told them that they simply weren’t smart enough to understand every time they misread me, or replied to them condescendingly (“it’s ok, I don’t expect you to know these things”), or said “that’s ok, you’re only neurotypical.” Imagine if I told them that they were rude and inappropriate whenever they made eye contact during a conversation, or that they weren’t good at interpreting a task literally. Imagine that I used their lack of “theory of mind” as a weapon to negate their neurotype and told them that their behavior was not acceptable, or compared them to a child for smiling at people and making small talk.

I know likely reasons that autistic people look down at the floor – they may be trying to process auditory information better, may be looking at a pattern or something moving on the floor, may be trying to prevent themselves from being overwhelmed from movement of other people around them, or may just be daydreaming and thinking about something else entirely from what was going on in the room, a what-if scenario, or thinking about something they read or are interested in. Of course I’m not saying all autistic people are the same, or that I would read autistic people right all the time, but I’d definitely get much more right compared to reading a neurotypical person. Someone who is not autistic and doesn’t know about autism may not know that moderate sound can actually hurt your ears, or that you can be overwhelmed in a room of 4 people talking quietly, or frustrated by the randomness of some sounds (ticking clock + pen clicking randomly, people shuffling chairs, people breathing), or the buzzing of the lights.

But does that mean that neurotypical people have a theory of mind issue?

(no, and neither do autistic people).

Autistic people have theory of mind for other autistic people. Neurotypical people have theory of mind for neurotypical people, not for autistic people.

Neurotypicals have a communication and education issue.

We do not have a “theory of mind” issue.

I hope non-autistic people start listening.

Resources

Heasman, B., & Gillespie, A. (2017). Perspective-taking is two-sided : Misunderstandings between people with Asperger ’ s syndrome and their family members. Autism, 1–11. http://doi.org/10.1177/1362361317708287

Employers may discriminate against autism without realizing it. The London School of Economics and Political Science. http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/equityDiversityInclusion/2017/08/employers-may-discriminate-against-autism-without-realising/

You make some excellent points. It’s definitely true that people’s preconceived and inaccurate ideas about autism influence the way that they interact with autistic people. Once you tell someone that you are autistic, everything you say or do will henceforth be interpreted in a certain way and there’s nothing you can do about it.

I was diagnosed recently, aged 49 and have recently come to the painful conclusion that I’m better off keeping my diagnosis secret from all but close friends and family, for this very reason.

LikeLiked by 2 people

That’s really unfortunate. I have had luckily quite a supportive family (one thing is that if you’re autistic, you may very well have an autistic family or neurodiverse famiily – almost my entire family is neurodiverse). For me it actually made me communicate better and get closer to my dad, because he is likely an undiagnosed autistic as well. It is hard to decide these things and you never know how people will respond, which always makes disclosure a scary one. For me it has gone quite well, besides a few bumps in between. At least they are willing to listen and learn from me.

LikeLike

Just came across your blog and noticed that this post is very similar to one I wrote just a few days ago, so I’ve added a link to it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks!

LikeLike

I really recommend the paper “Empirical Failures of the Claim That Autistic People Lack a Theory of Mind” from Gernsbacher (2019).

The experiments on which this paint-of-the-mind thesis was based in the 1980s could not be replicated and have been refuted several times.

The meta-study by Gernsbacher is from 2019, and unfortunately this refuted ToM fairytale is still repeated over and over again in the academic context.

Full text:

LikeLiked by 1 person

Here is the full text to the paper “Empirical Failures of the Claim That Autistic People Lack a Theory of Mind”:

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31938672/

LikeLiked by 1 person

I really enjoyed this article but just wanted to point out: I don’t know how many episodes or seasons you watched of the Good Doctor, but I watched all 4 seasons and I enjoyed that throughout the episodes, Shaun actually has a character development and shows a more complex autistic experience. I actually thoroughly enjoyed this show (I am autistic) and feel that it can help some people become less prejudiced against autistic people. You wrote:

“or their savant-ness used as inspiration porn with the backdrop of being autistic (The Good Doctor). These characters are consistently portrayed as off-putting, embarrassing for others to be around, selfish, incapable of learning from experience, lonely, and struggling to make friends, or not caring whether they have any.”

Shaun is sometimes portrayed as off-putting or embarassing for others to be around (especially in the beginning), but overall throughout the different seasons, people learn more about him and he learns more about the people around him and there are less and less instances like this and people develop acceptance for him and how he’s different. The “selfishness” he shows sometimes, is actually shown to mean that he cares about others, it’s just in ways NTs don’t understand (e.g. when he forces Dr. Glassman.to find solutions for his cancer, even if Glassman wants Shaun to leave him alone, and Shaun just doesn’t stop, ignoring all pleas by Dr. Glassman, “selfishly” persevering). Shaun is shown to learn from experience, shown to care that he has friends and a romantic partner, etc. I really liked the different relationships between the characters that developed.

LikeLike